Written By: Joseph Haughton

The first thing God did was speak:

“And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light (Genesis 1:2-3).”[1]

Switch it around a bit, add some proper lineation, and boom! We have a poem:

“And the earth was without form,

and void; and darkness was upon the face

of the deep.

And the Spirit of God moved upon the face

of the waters. And God said, Let there be light:

and there was light.“

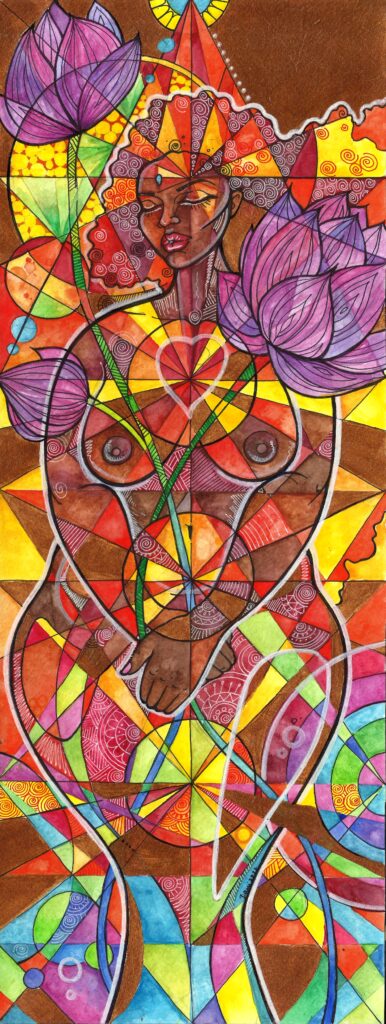

When I think of poems, I think of light refracted, bent over itself and falling into the abyss – where it illuminates going all the way down. Poetry helps us to understand both the world and ourselves. With it, we have a way of peeling back our layers to see what is on the inside.

“God’s light shone upon the abyss

and the monsters within writhed

under its might, knowing it not, knowing

only whence it came.“

Poetry is impossibly old. I like to think that poetry came into the world when a caveman noticed that repeating the same grunt three times in a row made it sound better to his lady friend. (Ugh. UGH. Ugggh. – the first poem.) Our language has developed a little more than that, but our attachment to poetry hasn’t changed.

Not only is poetry one of the oldest art forms, but it’s also one that people come back to over and over. It’s not uncommon for someone to find a poem that’s esoteric when they’re young and then revisit it when their older, only to find that its matured with them. Many people carry poems with them everywhere they go, and some collect them like so many little, intimate puzzle-pieces.

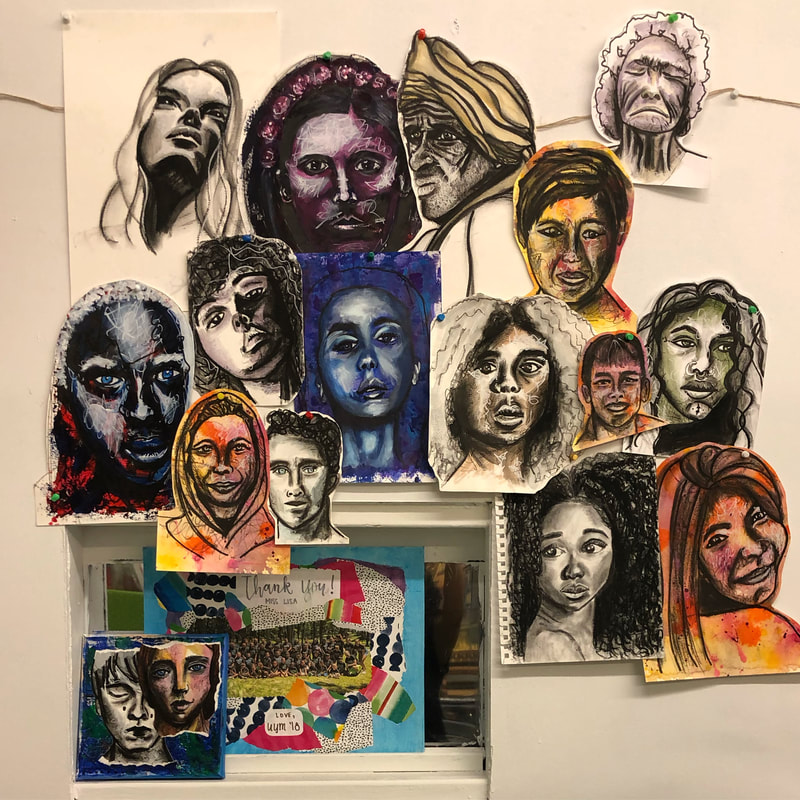

All of human experience is framed by our language. Language is inherent to humans in a unique way, and poetry represents the intentional use – even the mastery – of language for the purposes of making the symbolic vernacular. Poetry lets us capture the aesthetic essence of our lived experience in words. Poetry lets us write, read, and hear beautiful things. As such, poetry is wrapped up in all our acts of communicative creation: speeches, books, dialogue, songs, etc.

Imagine your favorite TV show or movie, but with worse writing, like “I don’t like sand. It’s coarse and it gets everywhere” (aside: that’s a deep-cut joke. If you know, you know.) Listen as an elected-official rambles through the public health advisory, changes subject three times, and leaves you feeling both scared about your own wellbeing and concerned about his mental functioning. Compare that to the heights the culture reached when Beyoncé released Lemonade. When she said, “True love breathes salvation back into me / / with every tear came redemption / / and my torturer became my remedy,” it was a word for the ages[2]. All three examples hinge on the use of language the right way, and poetry has a lot to say about that.

Poetry has long been a means for people to spread messages about their emotions. There are innumerable poems on love, mourning, sex, pain, strength, joy, nature, religion, … there’s something for everyone, about every topic. We all have the classic memorized: roses are red / / violets are blue / / [insert something cute here] / / and I love you. That poem captures an innocence that we all had once. Once upon a time, we were all just kids with crushes.

But, frequently, the poetic veers into the harsh, and poetry is crucial in talking about that too. The story goes that when J. Robert Oppenheimer, the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory that eventually produced the atomic bomb, saw the weapon’s first detonation, he recalled a verse from the Hindu Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”[3] He’d later describe the moment, saying “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.”[4] Those words marked a new age in human history, one we still haven’t gotten out of.

[1] The Holy Bible. Authorized King James Version, Thomas Nelson Bibles, 1990.

[2] Beyoncé. “All Night.” Lemonade, Parkwood Entertainment, 2016. Spotify, https://open.spotify.com/track/7oAuqs6akGnPU3Tb00ZmyM?si=wQPxiLt_R36_2kPVBVM3mQ

[3] qtd. in Temperton, James. “’Now I Am Become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds’. The Story of Oppenheimer’s Infamous Quote.” WIRED, WIRED UK, 9 Aug. 2017, www.wired.co.uk/article/manhattan-project-robert-oppenheimer.

[4] ibid.

Excerpts from Haughton’s Guide to Writing the Stylish and Insane, 3rd Edition

By: Joseph Haughton

… Tip 203: If someone walks in

and you do not cover up your work from embarrassment,

then you are not being honest enough.

Remove one article of clothing and continue writing.

Hold your tongue with a thumb and an index

and be ridiculous for a time.

This posture means you will be physically unable to lie.

Rage and then be silent.

Wonder at ignorance –

at your ignorance –

play an old drum and summon

the miraculous. Promise them your wealth

and they will return your soul.

Writing should be accompanied by a shoulder ache –

like a heart-attack, but one entirely necessary for living.