Written By: Joseph Haughton

Venom in the fang turned my bones to dust,

and the abyss filled in me, a new void.

I, too, once went in the dirt.

Ashes, my name was ashes.

Poetry, perhaps like all art, is about us: it’s a mirror for us, and a container for ourselves. The very act of speaking makes the speaker. God was, and then He spoke creation, and thus became the creator. We are, and we speak love, and thus we become lovers.

With communication so essential to our lives, the language we use or don’t use shapes our narratives in intricate ways. Poetry is a matter of mastering that language, allowing us to learn, unlearn, and relearn the framing metaphors of lives. Poetry, an essentially rhythmic form, settles deeper into the mind than regular words might. Through poetry, we gain access to the metaphors that help us navigate our lives: we learn that love is hot and that it’s akin to giving someone flowers. It asks and answers key questions: am I a flower? Am I a rock? Am I a weapon? What is the color of innocence? Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Let’s not forget that a summer’s day is frequently humid and sticky. (Love, admittedly, is like that).

Again God’s light broke upon the waves,

I cried out and the monsters within writhed.

God relented and a quiet settled

on the waters. New names – struggle.

Poetry provides an intimacy that links the social to the individual. As we think about what poetry is to society – to us – we must eventually think about what poetry is to the individual – to me. Great poets are able to take broad and big ideas and make them very personal. And appropriately so, because poetry reflects what is inside. Poetry is a means of speaking out to the world, in a process that often includes developing self-knowledge.

For me, that process meant developing my own identity while in college, during a bout of depression. The process was a fitful one; I found myself pouring words into my emotional wounds, hoping that something – anything – would resonate. Over time, it enabled me to shake off my malaise and move toward real development. Not only is the finished product important, but the very process of writing is one of truth-seeking.

Poetry became a way to confront the scary reality of life: trauma is impossible to escape, and the human condition is one that includes a lot of suffering, often at the hands of other people. Healing from that is a difficult process. The great thing about writing is that it places the power to define pain in your own terms. You get to decide how it ends. And if you don’t like the ending, you get to change it.

A darkening: the moon rises on the horizon.

Its shadow engulfs everything. A star

shines and sings a lonely tune.

Absence –

broken when another star peeks past

the cloud. Another, and another and now

a multitude.

***

Poetry can be a temperamental master. He sometimes wants perfection – sometimes poetry imagines harmony as the only truth. Nothing God created was not good. Thus, poetry is so often about finding harmony, order, tactful completion. Then again, he calls for the world as it is, which is to say, disharmonious. Sometimes, poetry is only about the faithful reproduction of the discord of life. Secretly, poetry wants to discover that disharmony is just another form of harmony, that disharmony in the world meets disharmony in the writer, and creates harmony in the art.

Life as a poet is life knowing that everyone else is a poet too, in their quiet moments (and their loud moments, and their ugly moments, and their beautiful moments and especially their horny moments). Poetry is everywhere all the time. A good poet just picks out the poetry that matters in the relevant situation. A good poet knows that there is so much poetry that goes unstated. It wraps itself over and over, syllable upon syllable, precept upon precept, to take shape as the other people we meet.

As a poet, you just keep pouring and pouring into the void, hoping something will stick with somebody somewhere. And sometimes, the only thing you have is words. All you can do is talk. Sometimes that is enough. Frequently, it is not.

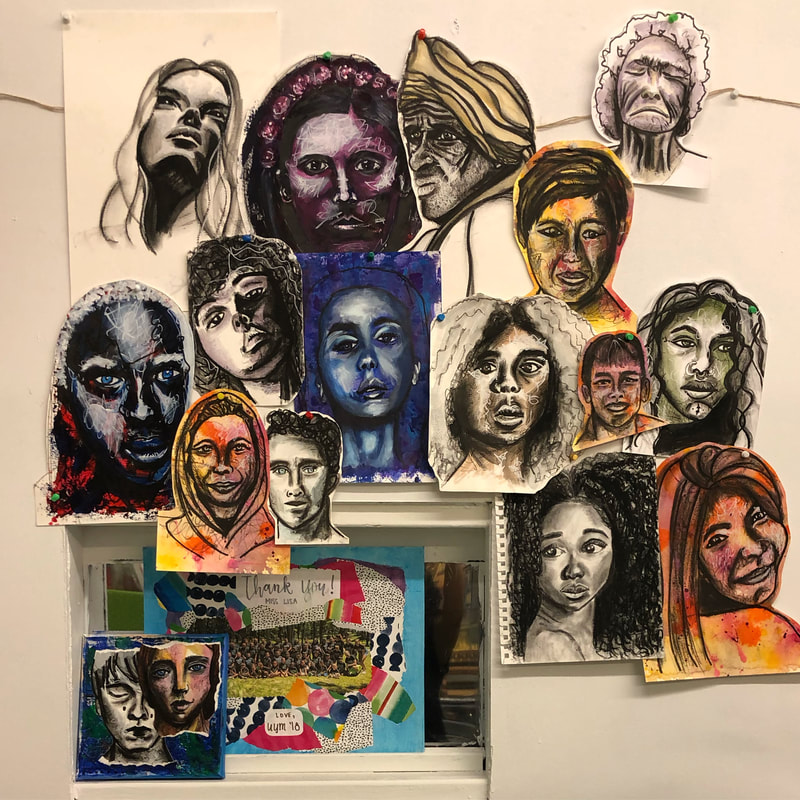

Portrait of my therapist as a black woman

By: Joseph Haughton

When on the left side, her half-smile is a cautionary tale

to those that would mistake her joy as their own

and her favor as their boon;

when on the right, it is an invitation

to sit and to speak and to laugh, if you will;

she chooses to share the space with you.

Her eyes are like vivid tidal pools

one stumbles upon in the sand

that give pause and cause ponderance

on lives you’ve lived before.

They are like lucid night sky dreams of flowing streams

in which your reflection is seen

and your mind played out in the open air

of a small room.

Her skin is in the Platonic form of brown;

it’s cinnamon, like Christmas sticks, mixed with

hickory, like the cookout smoke, mixed with

caramel, like the salted of the Earth, mixed with

bronze, like the Greeks, mixed with

umber like the rage.

Her hair is the sun rising atop a crown during an eclipse –

blacked out but in its strands, pride of ancient people who would,

if needed

chant the very moon out of the midday heavens.